Some ideas seem great at first but turn out to be incredibly bad in hindsight. I reviewed such an idea today.

Background

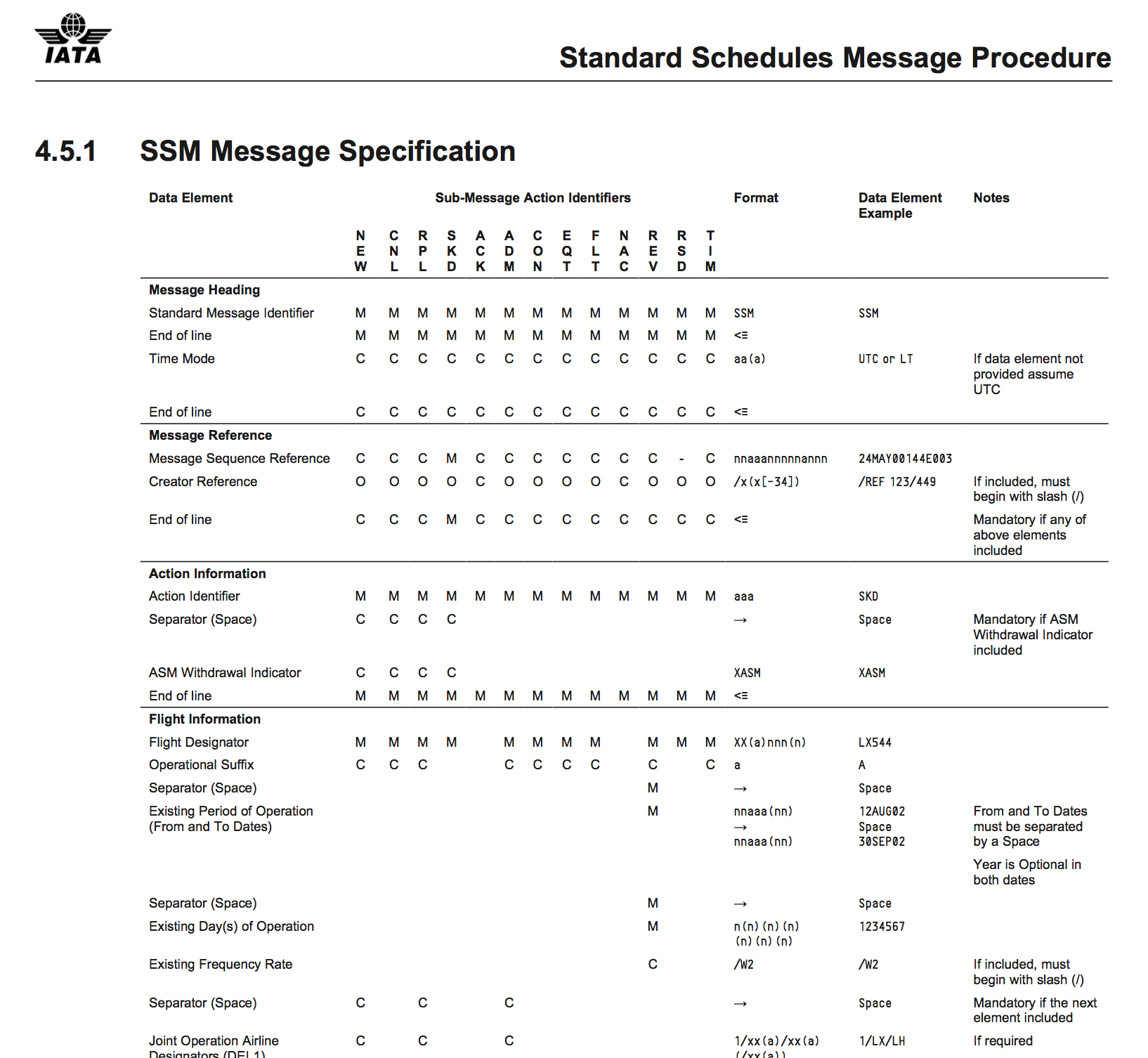

The task was to store flight information in a database. The information is transmitted via the IATA SSIM format, which standardizes messages with about 70 different fields. There also are various different types of messages, all of which might contain any of the 70 fields. An example: Airlines can publish their Standard Schedules Messages which contain the seasonal flight schedule, i.e. routes they usually fly on which days of the week. Exceptions from this get their own message (using different fields). Unforeseen changes are published via the Ad hoc Schedules Messages which, of course, use different fields as well. And then there are Movement Messages (from the Airport Handling Manual AHM) which contain the actual information on what each plane does. All of these messages make up a flight: The schedules, the ad hoc changes and what actually happened. The contents overlap but rarely match. In object oriented thinking, this would be extremely easy: You have an abstract message class, implementations for SSM, ASM and MVT and further classes that extend each of these for special cases.

Efficiently storing this in a database however is not that easy. You’re bound to wind up with a horrifying amount of columns and an awful lot of null entries. The contents will resemble the specification which lists all the elements each message sub-type must or might contain:

MESSAGES

| message_id | sender_id | foo | boo | tip | bli | bla | blubb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 9 | ‘bar’ | null | ’top' | null | null | null |

| 13 | 9 | null | null | null | 1 | 2 | 42 |

Why not…?

Yes, this structure is the reason someone invented document-oriented databases. However it is the only information that would require us to leave the relational world and operate yet another service. Also, the contents are tightly integrated into a lot of other tables, and we love referential integrity.

Storing key-value-pairs in a relational database

You can store key-value-pairs in a database, for example like this:

MESSAGES

| id | sender_id |

|---|---|

| 12 | 9 |

| 13 | 9 |

VALUES_TABLE

| id | key | value | message_id |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ‘foo’ | ‘bar’ | 12 |

| 2 | ’tip' | ’top' | 12 |

Now in our case the keys are well defined, so you will have a lot of redundancies there. The idea I was reviewing extracted the keys into yet another table:

MESSAGES

| id | sender_id |

|---|---|

| 12 | 9 |

| 13 | 9 |

VALUES_TABLE

| id | key_id | value | message_id |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ‘bar’ | 12 |

| 2 | 3 | ’tip' | 12 |

and

KEYS_TABLE

| key_id | key |

|---|---|

| 1 | ‘foo’ |

| 2 | ‘boo’ |

| 3 | ’tip' |

| 4 | ‘bli’ |

| 5 | ‘bla’ |

| 6 | ‘blubb’ |

Wonderfull! No nulls, no redundancies, no more than four columns! This idea sounds great!

…and hell breaks loose

Database design fails can live in production for a long time until they get noticed. And that’s when all your precious data is already put into this bad scheme.

In the case of the above solution things get ugly the moment you query for something specific. For example all messages where ‘foo’ is ‘bar’:

SELECT * FROM MESSAGES m

JOIN VALUES_TABLE v ON m.id = v.message_id

JOIN KEYS_TABLE k ON v.key_id = k.key_id

WHERE k.key = 'foo'

AND v.value = 'bar'

As opposed to

SELECT * FROM MESSAGES m WHERE m.foo = 'bar'

The problem only grows when you create this query from your business code: You have to get the ‘foo’ string from somewhere:

- You might hard code it. Yak.

- You might create an enum replicating the

KEYS_TABLE. Until that table changes—and beware, not the structure, but the content! - You might be extra clever and save a

JOINby using thekey_iddirectly!

My best guess is that you’d wind up with all three options scattered in your code. Good look.

The solution / workaround

As I said in the beginning, tables with many columns and null entries might not be very elegant, but databases and developers are used to them. Also, document-oriented databases were invented for a reason. This might just be that reason.

There is another option: vertical partitioning. Especially in this use case, where there is a specification that provides the information on where to split:

MESSAGES

| id | sender_id |

|---|---|

| 12 | 9 |

| 13 | 9 |

MESSAGES_PART_1

| id | foo | tip |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | ‘bar’ | ’top’ |

MESSAGES_PART_2

| id | bli | bla | blubb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 1 | 2 | 42 |

Let’s check for our query:

SELECT * FROM MESSAGES m

LEFT JOIN MESSAGES_PART_1 p1 ON m.id = p1.id

LEFT JOIN MESSAGES_PART_2 p2 ON m.id = p2.id

WHERE p1.foo = 'bar'

Well… it doesn’t suck as much. However, if you’re on the INSERT side of the database you’re gonna have a bad time…